John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place: In A Place Everyone Can Hear You Scream

I sometimes have the dream where I can’t scream. I’m in some kind of peril, generally I’ve been under pursuit and the shadowy figure has me in his murderous clutches, and I am terrified but when I open my mouth to cry out – nothing, just an intense, compressed silence. I’ve had that dream often enough that there was part of me that was actually concerned that I wasn’t a screamer, that I could be in actual danger in the waking world and at the critical moment, I would have no voice. I had been under the false impression that screaming was something someone decided to do in an emergency. But thanks to my loving husband who thought it would be a fun prank to leave our standee of John Boyega in the shower behind the curtain, I learned firsthand that to shriek in terror is an involuntary reflex from your brain perceiving a threat – like a person in your shower that is not supposed to be there. What was supposed to be a silly joke was an impromptu test to my internal alarm system. It works just fine, by the way.

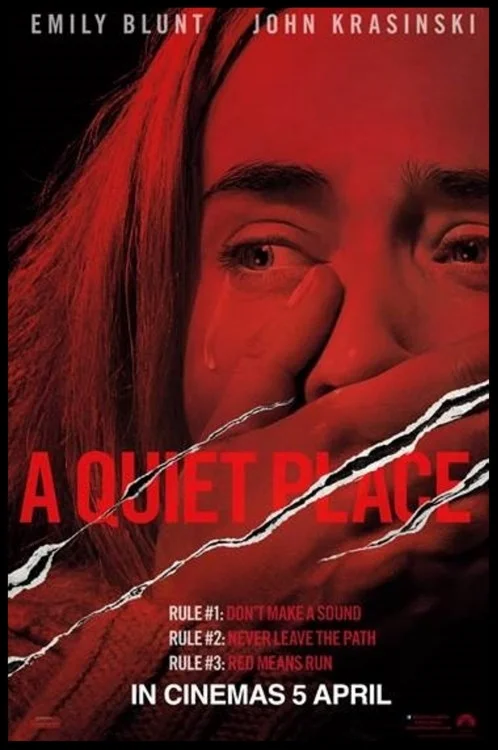

The ability to scream serves more emergency functions besides being an autonomic klaxon. Crying out is how we warn each other, find each other, alleviate pain, express sorrow, but in John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place that biological tool is off limits. There has been a global infestation of blind creatures that hunt primarily through their extraordinarily acute hearing and even the slightest noise will summon them. 89 days after the scourge, the family has adapted to live in a perpetual state of stifling quiet. They communicate primarily in American Sign Language, they walk cautiously, they handle objects delicately, and they’ve modified every activity to be done absolutely silently. Lee (John Krasinski) and Evelyn (Emily Blunt) spin their wheels creating contingency plans for when the accidental sound brings on the beasts in hope that they can keep their three kids – Regan (Millicent Simmonds), Marcus (Noah Jupe), and Beau (Cade Woodward) – safe.

For all of their vigilance, life inevitably makes noise, and the monsters are drawn to the family. They are in the Abbotts’ home, lurking with their evolutionarily honed ears agape and oozing – like they’re salivating for sound. The screams that cannot be made just seem to gather and create tremendous pressure that is going to blow like a failed gasket. Having the creatures be attracted to sound is an ingenious premise because it heightens the audience’s senses. We start looking at the screen really hard and listen even harder priming us for misdirection and the dreaded jump scare. The film does a masterful job orchestrating anticipation. It fluctuates and abates but is never relieved. There is not one second in this film where things are fine, no matter how much those parents pretend they are.

Despite the terrible man-eaters of mysterious origin, A Quiet Place is a meditation on the lengths that parents will go to create normalcy for their children. They go over safety measures, they paint the non-creaky floorboards, they soundproof what they can, they take every conceivable precaution, and then they have dinner as a family, or play a game, or teach from a textbook, and project an illusion of calm so that their offspring can believe that maybe there is a future to look forward to. This feels like a tremendously personal movie for director/co-writer/star John Krasinski and Emily Blunt who are a family with children of their own. To raise kids in a time of uncertainty can be really scary, but it is the most worthy thing one can do.

I left the theater with my nerves utterly jangled, but exhilarated. As a director, Krasinski is adept at creating tension in a single shot – batteries, a nail, an egg timer. The silence keeps your mind reeling with dreaded possibilities that keep your eyes peeled and your ears pricked. The casting of the family is impeccable and grounds the story. You can’t help but see yourself and your own loved ones in the same (hopefully) impossible predicament. Millicent Simmonds is a nuanced young actor and a paradigm for why people with disabilities should represent themselves, rather than someone doing an impression. If you haven’t already – though the $50 million opening box office is a strong indication you have – go see this movie in the theater with a crowd. But don’t get the popcorn. Not unless you want the monsters to get you.