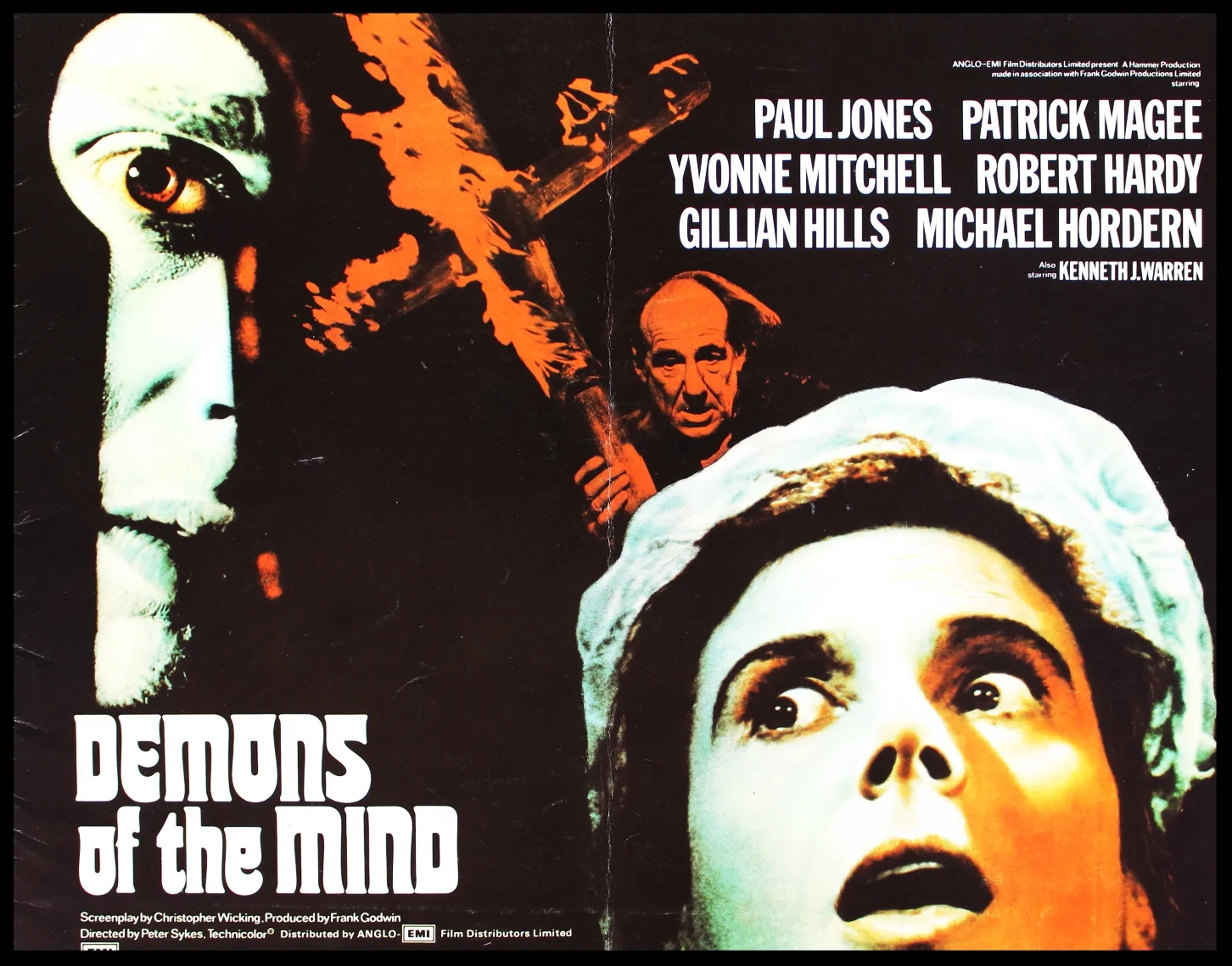

Demons of the Mind

I always feel inexplicably cheered when the same old woods crop up in a Hammer movie. Most of the time I don’t know where I am or even what, quite frankly, is supposed to be going on. But whenever I’m watching a movie and a clattering carriage careers through those Hammer woods like an arthritic bat out of hell, I know where I am. When some poor sod’s feet won’t carry them away fast enough from a monster through sparse and unhelpful trees, I know what’s going on. I am content because I’m watching a Hammer film, and that sort of existential certainty doesn’t come along every day, I can tell you.

It’s a comforting familiarity borne of necessity, granted, with Hammer’s studios being right next to a lovely forest. Quite handy, if you think about it, when you’re making your period horrors. Woods are woods, no matter the century, or country for that matter. So whether you want Dracula roaming England in the 1970’s, or Transylvania in the 1870’s, stick some woods around him and Bob’s your bloody uncle - a set. But in one Hammer film the woods are more than just some free spooky atmosphere that’s lying around. In Demons of the Mind the woods get to have their day as an honest-to-goodness metaphor; they become the dark and unknowable places where we hide our, well you know, demons of the mind.

See, in the middle of the woods there’s an insane family living in a big old mansion. And one of them is sneaking out and murdering women from the village. Is it the father who’s keeping his adult children drugged and locked up convinced his madness has become theirs? Is it the son who has an aristocratically inappropriate thing for his sister? Is it even the daughter whom every victim worryingly resembles? Whichever one of them it is, they are all lost in the woods; the real murderer hidden from the village, each other, and even from themselves. The audience can’t see the murderer either, their face always hidden by impenetrable trees.

And there’s some other rather splendid metaphors too. The dad, played by Robert Hardy, is always on the balcony looking through a telescope, watching for the inevitable mob that he knows will be coming for them all one day soon. It makes the mansion feel like this half abandoned ship in an ocean of trees, hoping to evade an approaching enemy. Hardy always had a bit of a posh Admiral thing going on, I always felt, which adds nicely to the overall effect. And late on in the movie, the children’s jailer is stabbed to death by their own keys which, while not a very subtle metaphor, is a pretty fun one nonetheless.

There’s also some sneaky fun poked at the origins of Christianity, and who isn’t on board with that? See, the rather magnificent Michael Hordern is the first Christian priest seen round these parts, and the village is even carrying out an ancient Pagan ritual when he arrives. Now, normally in a Hammer film, the Priest would be the voice of reason, maybe even some sort of mild detective work would take place before he would figure out who the murderer was. But instead, the Priest turns out to be the biggest swivel-eyed looney of them all, and co-opts the pagan ritual in the name of Jesus to bring down the noble family he immediately points the finger at. No deduction, no reason, just straight to the overthrowing of the Godless ruling class. It all ends with a crazy-haired Michael Hordern driving a giant burning cross into evil Robert Hardy’s chest. And that is one memorable scene, let me tell you.

I really wish the rest of it was. It’s not a bad film by any means, it’s just nowhere near the sum of its parts. There’s too much worried pacing, not enough weird secrets, and definitely not enough Michael Hordern, which means not enough scenery chewing. In fact, now that I think of it, that’s the real problem with this movie, which is about madness after all - there’s not nearly enough wild overacting. Everyone should be getting crazier and crazier as the film goes on. The demons of the mind should crawl out of those metaphorical woods and start taking over the ship. The movie should explode into a chaos of insanity and murder and lust, as the things Hardy has been trying to keep a lid on for all these years can no longer be contained.

But unfortunately, none of that really happens. They all start quite mad, and keep being quite mad, right up until the end.

All things considered, it’s just a bit bloody dull for a film about paranoia, incest and homicidal mania. But it looks very nice, there are some genuinely fun ideas, and Hordern’s cameo is worth the price of admission alone. And it’s nice to see those old woods of Hammer finally get to play the metaphor they always deserved to be. Nobody knows how to use some woods and an old house better than Hammer after all. And you can never go too far wrong if you stick to what you’re good at. Speaking of which…

Another pint?