At Twenty Five: Heavenly Creatures

“It’s all frightfully romantic”

By November of 1994, fourteen-year-old me was very familiar with the work of Peter Jackson. Teenage gore-hound that I was, I knew every blood-soaked second and every line of lunatic dialogue of the incredible Dead Alive (aka Braindead), as well as the rampant depravity of the much-harder-to-find Bad Taste. Jackson’s career began to turn in 1994 - as his work became a bit more mainstream - eventually leading to The Frighteners in 1996 and, of course, The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which netted him several Academy Awards. LOTR was, in a lot of ways, the horror genre taking over the world – Jackson with his horror roots making a monumental epic for New Line Cinema, a production company known in Hollywood as “The House that Freddy Built.”

But I digress. We’re not here to talk about LOTR. We’re here for Heavenly Creatures.

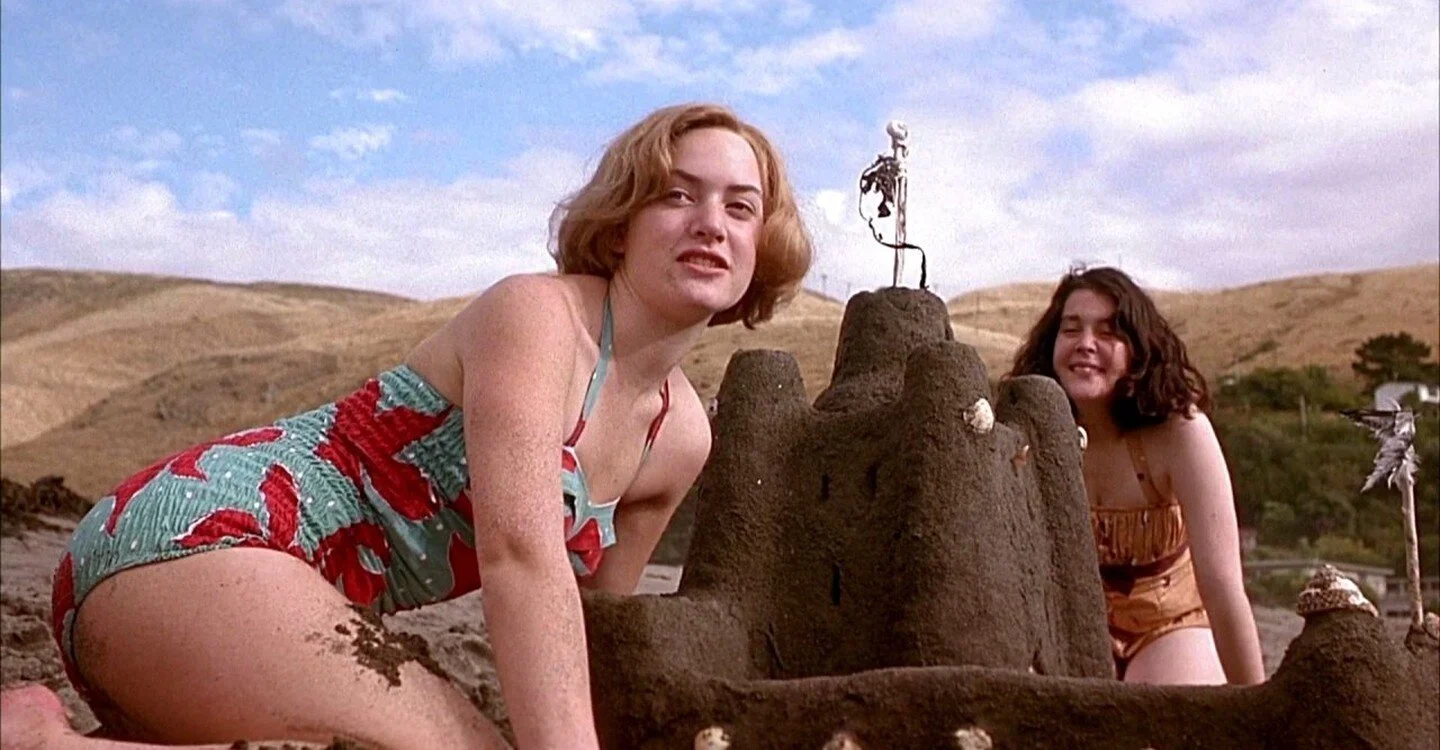

Kate Winslet and Melanie Lynskey in Heavenly Creatures

Heavenly Creatures bridged the gap for Jackson, taking him from low-budget horror into the mainstream, but Jackson doesn’t lose site of his roots. Painted in a palette of Argento colors and Raimi camerawork, Heavenly Creatures tells the story of the obsessive friendship between two teenage girls – Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme - in the repressive echo of the British Empire that was Christchurch, New Zealand in the 1950’s. The world of Pauline and Juliet is a world before Elvis, where the big rock star the girls fawn over is tenor Mario Lanza, squealing and laughing in ecstasy as they waltz with each other through the stately rooms of Ilam, the Hulme’s estate.

Juliet is new to Christchurch; her father having just been named head of Canterbury University and the family moving with him from England. She is well-traveled and well-educated for fourteen and possesses a vivid imagination and talent for world-building, intending to write and publish a fantasy novel. The world that she creates is detailed and, in her mind, very much alive.

It is just such a world that the quiet, withdrawn Pauline (called Yvonne by her family – the first of a few name changes) has been waiting for longer than she realized. As the girls grow closer and closer, the shared fantasy world of Borovnia occupies more and more of their time, effectively freeing them from the restraints of their stuffy, stoic society. They create clay figures and give them the faces of the famous people they so adore – Lanza, James Mason and Orson Welles (much to Juliet’s horror).

Several times, the real world interrupts their dreaming – Juliet contracts tuberculosis and is hospitalized for a time; their parents – the direct symbols of oppression and disaffection – attempt to keep them apart, fearing that they may be in love with each other (homosexuality was illegal in New Zealand until 1986, and considered a mental disorder until 1972). With each interruption, the girls become more separated from the world around them, and more defensive of Borovnia and of their love for each other. When a divorce threatens to separate the girls forever, Gwen and Deborah (as they call each other) devise to commit a truly shocking act of violence.

In the early phases of Heavenly Creatures, it is hard not to fall in love with the main characters and their romance (of a sort, the real Juliet Hulme swears there was no sexual relationship). But viewing this as an adult, it’s also difficult to not recognize the parents’ struggle – specifically Pauline’s mother, Honora, who wants to relate but simply doesn’t know how. As the tension builds, and the end becomes more and more clear, you find yourself near screaming “Talk to each other, for Chrissake, don’t let this happen!”

But it happens. Because it happened.

So much of this story feels like fantasy, so lost are we in the innocent love that these two girls feel for each other, that we forget the grim truth until it is too late. This is slight-of-hand filmmaking, distracting us with lush romanticism before knocking us flat with brutal reality. Jackson makes us forget that we’re watching essentially a true-crime drama until we’re well past the point of no return. As storytelling goes, it is masterful.

Heavenly Creatures was also the film debut of Kate Winslet as Juliet, and Melanie Lynskey as Pauline. Both are staggeringly good as the obsessed teenagers. Ms. Lynskey was particularly amazing, the angry fire in her dark eyes as she glares at her repressive mother and the barely-contained glee as she envisions her family dying around the dinner table; she was, in turn, loveable, sympathetic, heartbreaking, and absolutely terrifying.

25 years later, Heavenly Creatures might carry more weight than it did upon release, as violence seem to become more and more commonplace, and the faces of both the victims and the perpetrators seem to be younger and younger. This is a story of disconnected youth unsure of why they aren’t accepted in the world as they are. It’s about finding someone to hold on to, someone who understands. And, when the world threatens to take that away, they lash out in the what they see as the only way they have left. The immediacy of their problem, in their obsessed and short-sighted minds, demanded an immediate solution, and the finality of that solution never occurred to them.

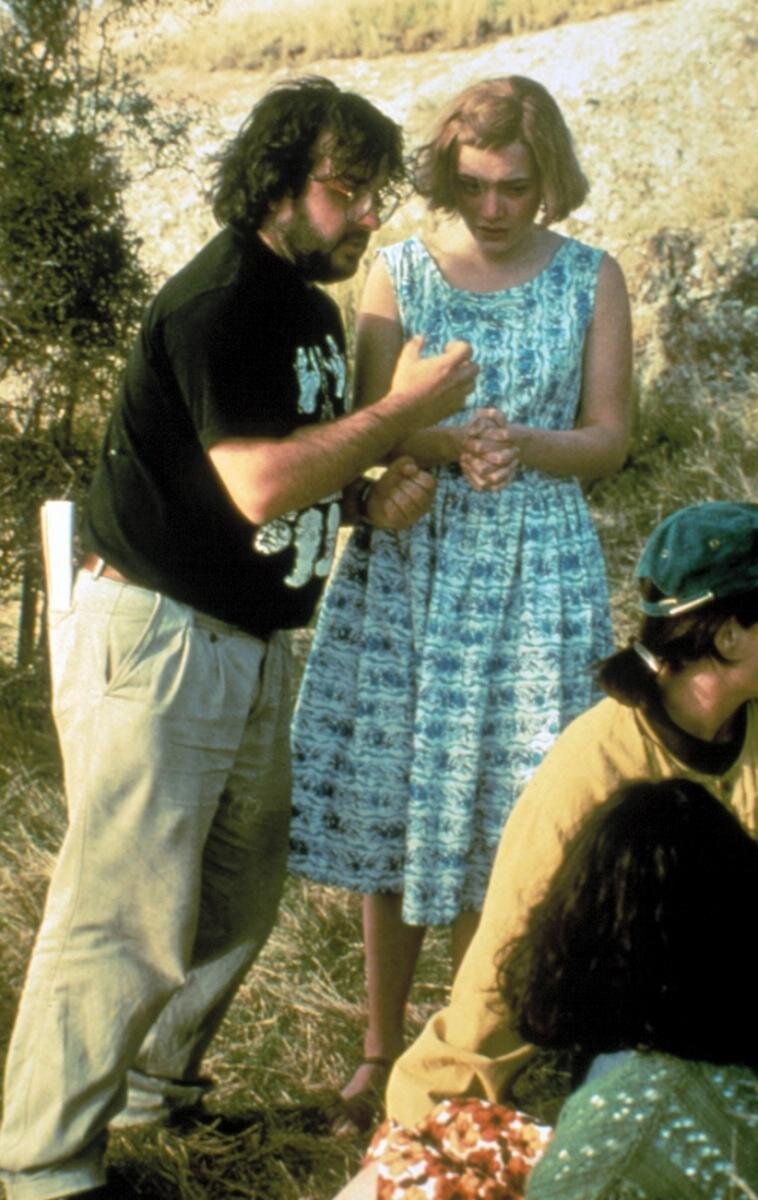

Peter Jackson and Kate Winslet on the set of Heavenly Creatures

Peter Jackson has had a unique career up to now, varying from splatter-heavy low budget horror to Award-winning blockbusters. Heavenly Creatures stands out among this list - a one-off drama amongst the action and gore and battles and ghosts - a real-life horror story that chilled me and disturbed me far more than most horror fare. It’s haunted me for days since watching it.

Near perfect. 10/10